Physicists at the University of Southampton, UK, have unveiled a groundbreaking experiment, successfully creating the first laboratory-based ‘black hole bomb’. This achievement brings to life a phenomenon that has long been the subject of theoretical exploration.

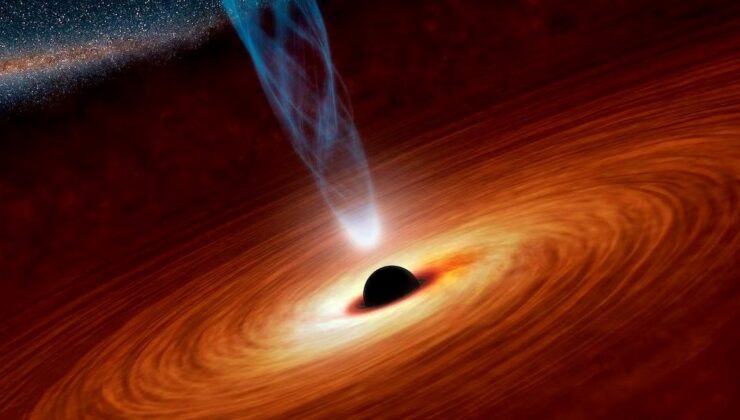

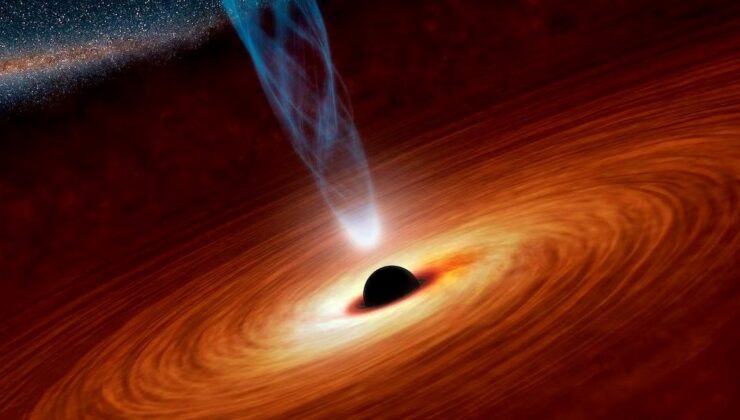

The concept of a ‘black hole bomb’ revolves around the potential to harness and amplify the rotational energy of a spinning black hole. By strategically surrounding it with a reflective mechanism, akin to a ‘mirror’, this energy can be accumulated until it culminates in a powerful explosion.

In their latest research, the scientists simulated this phenomenon using a black hole model in a controlled laboratory setting, an endeavor that would be impossible with an actual black hole in space. The underlying physical principles, however, remain consistent with those found in nature.

The roots of this idea trace back to 1969 when physicist Roger Penrose proposed the notion of extracting energy from a rotating black hole. He postulated that a particle closely skirting a spinning black hole could gain energy, a consequence of the principles outlined in Albert Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. This energy gain results from the black hole’s influence, which drags and accelerates the surrounding space-time.

In 1971, physicist Yakov Zeldovich expanded upon this concept, suggesting that similar effects could manifest in other environments. Specifically, he identified that light circling a rapidly spinning metal cylinder could experience a phenomenon known as ‘superradiance’. Zeldovich calculated that this effect would occur if the cylinder’s rotational frequency matched that of the light. However, achieving such speeds was deemed nearly impossible at the time.

Zeldovich further theorized that by encasing the rotating cylinder within a cylindrical ‘mirror’, a positive feedback loop could be established, leading to either the expulsion of energy or a dramatic explosion. When applied to black holes, this theory suggested the potential for a ‘black hole bomb’, capable of releasing energy on par with a supernova.

These concepts remained largely theoretical until the recent experiment led by Hendrik Ulbricht and his team at the University of Southampton. Their innovative use of a spinning aluminum cylinder and magnetic fields successfully demonstrated Zeldovich’s feedback loop in a tangible setting. The first prototype was constructed in 2020, as shared by Ulbricht with New Scientist.

The current setup involves an aluminum cylinder rotated by an electric motor, surrounded by three layers of metal coils, which generate a magnetic field rotating at a similar velocity. In this configuration, the coils function as mirrors, while the magnetic field mimics light. As Zeldovich predicted, this setup results in the emission of an intensified magnetic field from the cylinder.

“You direct a low-frequency electromagnetic wave into a rotating cylinder and observe an amplified return,” explained Vitor Cardoso from the University of Lisbon to New Scientist. “It’s truly astonishing.”

This pioneering experiment holds promise for enhancing our understanding of how actual black holes energize surrounding particles.

SİGORTA

4 gün önceSİGORTA

5 gün önceENGLİSH

14 gün önceSİGORTA

14 gün önceSİGORTA

14 gün önceSİGORTA

18 gün önceSİGORTA

19 gün önce 1

Elon Musk’s Father: “Admiring Putin is Only Natural”

11779 kez okundu

1

Elon Musk’s Father: “Admiring Putin is Only Natural”

11779 kez okundu

2

7 Essential Foods for Optimal Brain Health

11759 kez okundu

2

7 Essential Foods for Optimal Brain Health

11759 kez okundu

3

xAI’s Grok Chatbot Introduces Memory Feature to Rival ChatGPT and Google Gemini

11505 kez okundu

3

xAI’s Grok Chatbot Introduces Memory Feature to Rival ChatGPT and Google Gemini

11505 kez okundu

4

DJI Mini 5: A Leap Forward in Drone Technology

10472 kez okundu

4

DJI Mini 5: A Leap Forward in Drone Technology

10472 kez okundu

5

Minnesota’s Proposed Lifeline Auto Insurance Program

9704 kez okundu

5

Minnesota’s Proposed Lifeline Auto Insurance Program

9704 kez okundu

Veri politikasındaki amaçlarla sınırlı ve mevzuata uygun şekilde çerez konumlandırmaktayız. Detaylar için veri politikamızı inceleyebilirsiniz.